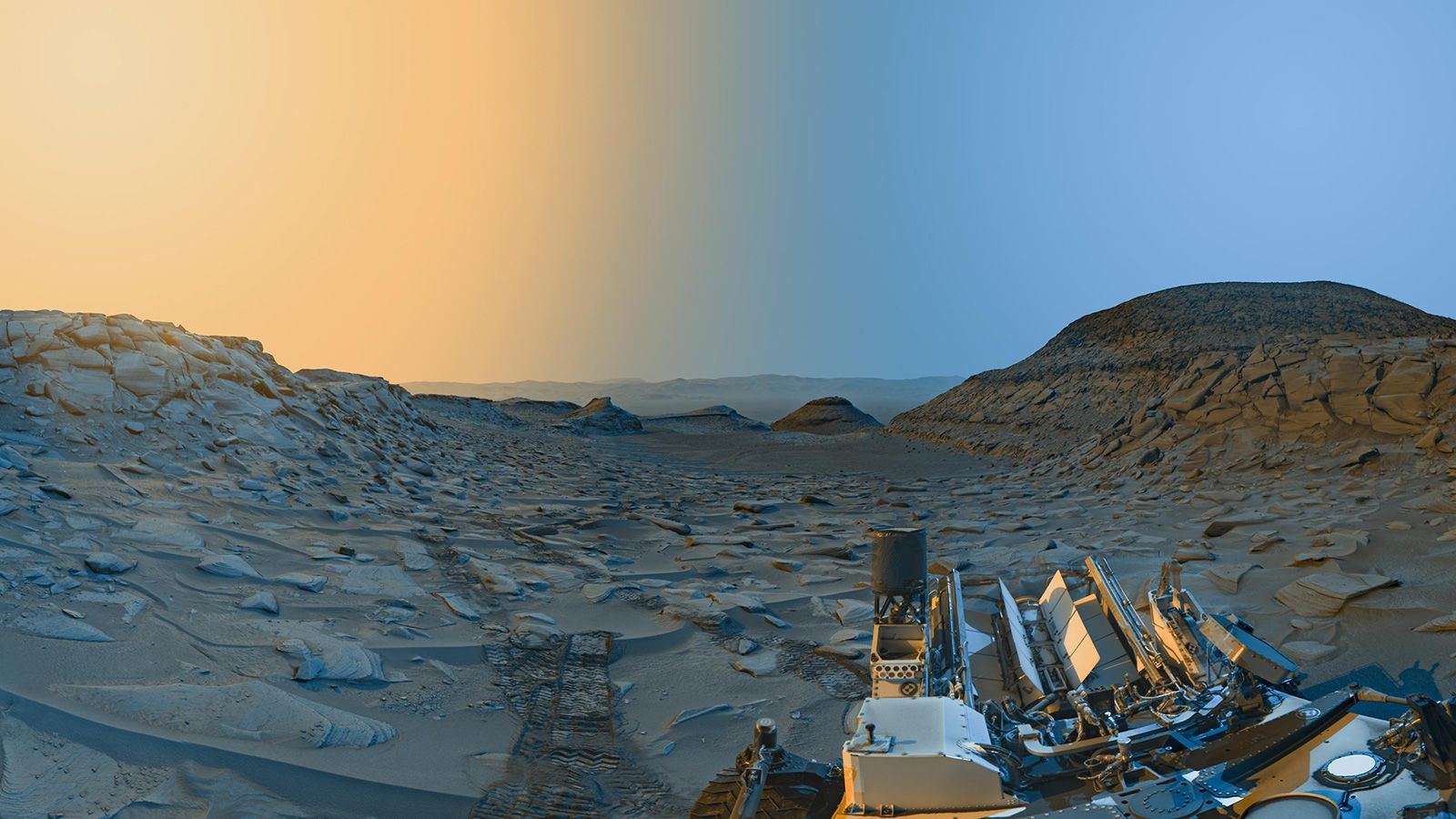

NASA’s Curiosity Rover Reveals Clues About Mars’ Warm and Wet Past

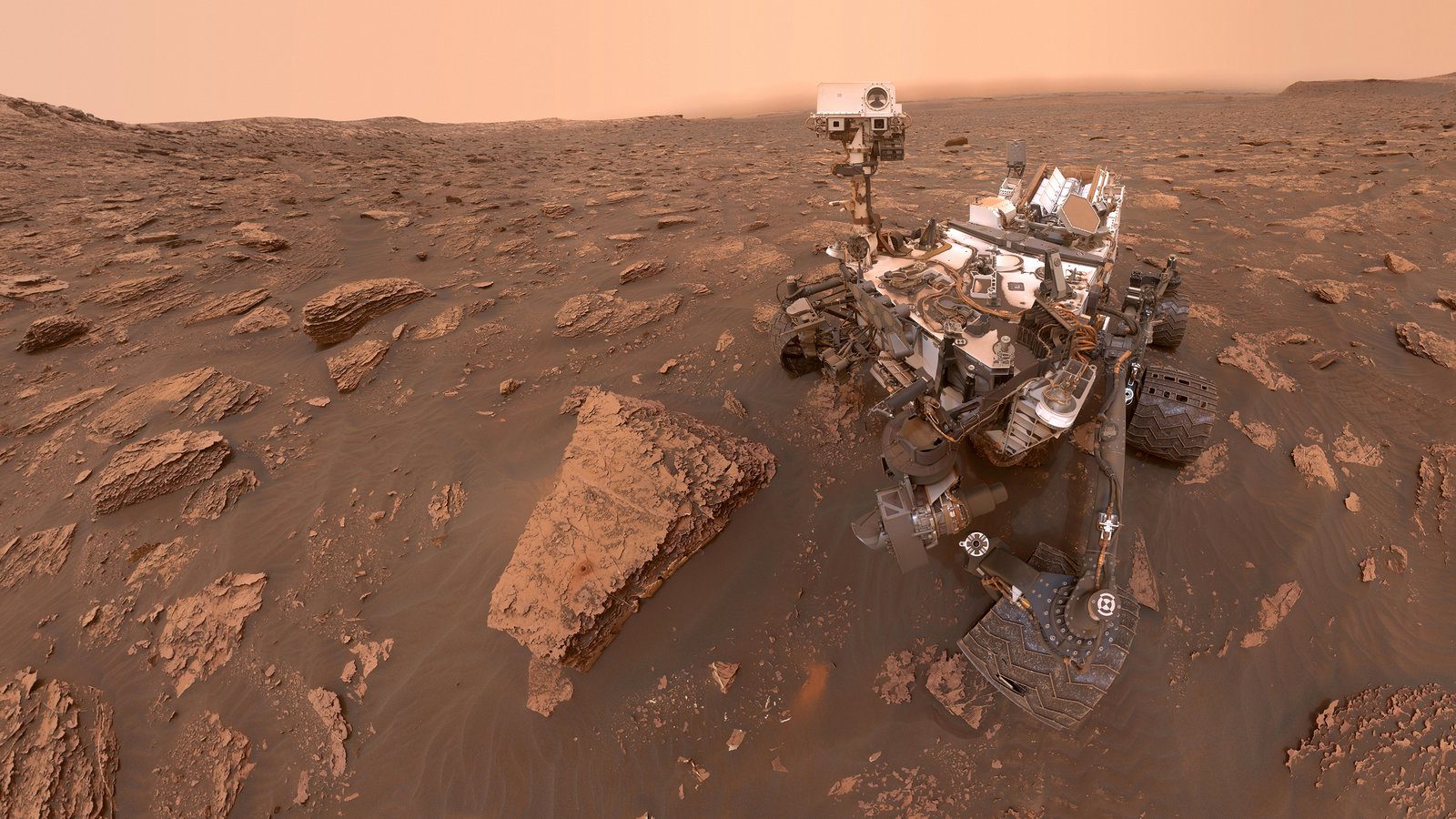

Mars might not have always been the dry, dusty world we know today. Thanks to new evidence collected by NASA’s Curiosity rover, scientists now believe the Red Planet may once have had flowing water and a thicker atmosphere. What tipped them off? A mineral called siderite, found in rock samples deep in Gale Crater.

What the Rocks Are Telling Us

During recent drilling missions, Curiosity pulled up rock samples with surprisingly high amounts of siderite—more than 10% in some cases. That’s not something you’d expect unless there was a lot of carbon dioxide and liquid water around when the rocks formed. The presence of this mineral hints at conditions that were likely warmer and wetter, a far cry from the cold and barren landscape we see today.

Carbon Dioxide That Vanished Into the Ground

Mars has long puzzled scientists. Its atmosphere is thin, yet early climate models predicted more carbon-based minerals should be present on the surface. This new find helps fill in the blanks. The data suggests Mars may have locked away large amounts of carbon dioxide underground. Since the planet doesn’t have plate tectonics like Earth, that trapped gas wasn’t recycled—and the atmosphere slowly thinned out.

Maybe Mars Wasn’t Always a Desert

The age of the rocks—around 3.5 billion years—lines up with a time when Mars probably had rivers, lakes, and maybe even shallow seas. These weren’t just quick bursts of moisture either; the minerals suggest a sustained period where the planet could’ve looked a lot more like early Earth. Piecing this together helps explain how Mars went from wet to bone dry.

What This Means for the Bigger Picture

Every new bit of data changes what we know about Mars. The possibility that it once had the ingredients for life is now stronger than ever. If water stuck around long enough, microbes might have had a shot. Curiosity’s discoveries are helping zero in on where we should look next, and how we should look for signs of ancient life.

Curiosity isn’t just finding rocks—it’s telling a story. With each new clue, we get a better picture of what Mars used to be. And maybe, just maybe, we’re inching closer to finding out if we’ve ever had company in the universe.